Figures

| Figure 1.1a.

Stages of the human male sexual response cycle |

| Figure 1.1b.

Stages of the human female sexual response cycle |

| Figure 1.2.

Relationship of phylogenetic and ontogenetic familiarity to initial-stimulus

appetence and stimulus discriminability |

|

Figure 1.3.

Distribution of the trait "discriminative ability"

in a hypothetical

population. Distribution of the trait "discriminative ability"

in a hypothetical

population. |

| Figure 1.4.

Oystercatcher reacting to giant egg (supra-normal stimulus) in preference

to normal egg (foreground) and herring gull's egg (left). |

| Figure 1.5.

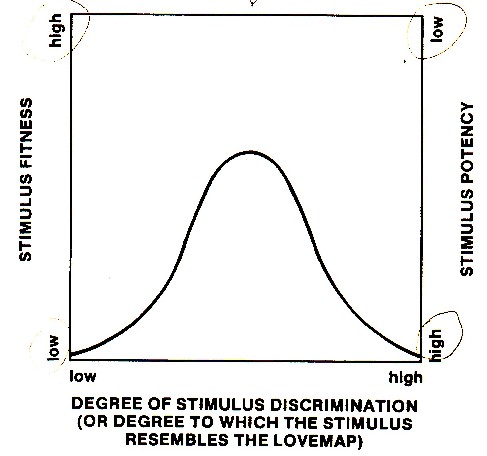

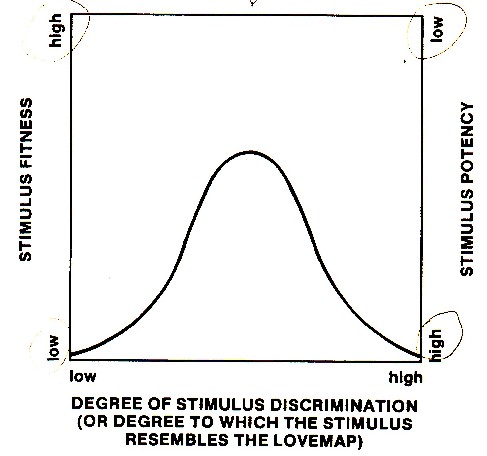

Relationship of stimulus fitness and stimulus potency to the degree of

stimulus discrimination in the perceiving individual |

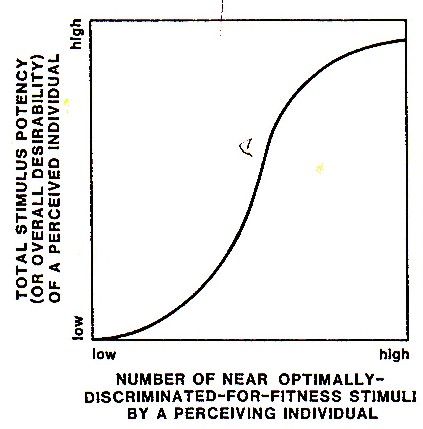

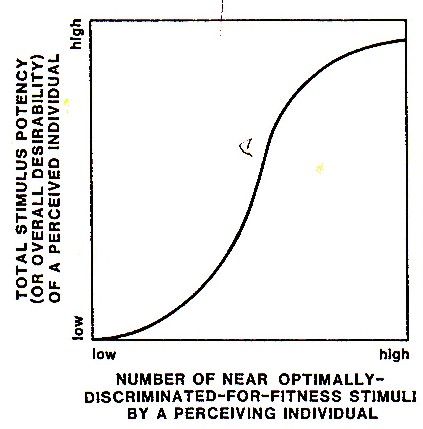

| Figure 1.6.

Relationship of total stimulus potency (or overall desirability) of a

perceived

individual to the number of near optimally-discriminated-for-fitness

stimuli by a perceiving individual |

| Figure 1.7.

Human heterosexual-male sexual releasing stimuli |

| Figure 1.8.

"Infant/child schema" of humans |

| Figure 1.9.

The relationship of relative age and relative gender of

individuals toward whom one is sexually attracted—represented by four

Attraction Quadrants |

| Figure 1.10.

Relationship of male androphilic and gynephilic

pedophiles and ephebophiles to male individuals with other sexual

orientations and to the Attraction Quadrants of relative-age and

relative-gender attraction throughout the life span |

| Figure 1.11.

Relationship of brain masculinization and brain

defeminization in the male to relative-age and relative-gender preferences

in the four Attraction Quadrants |

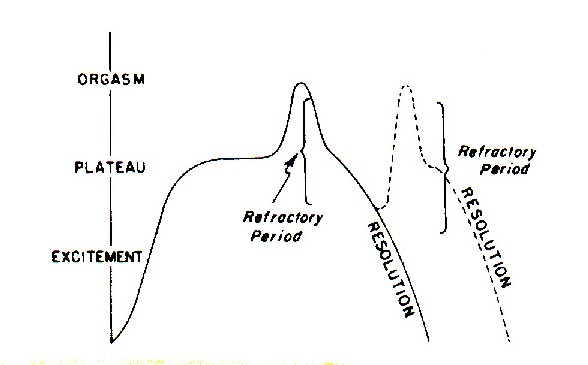

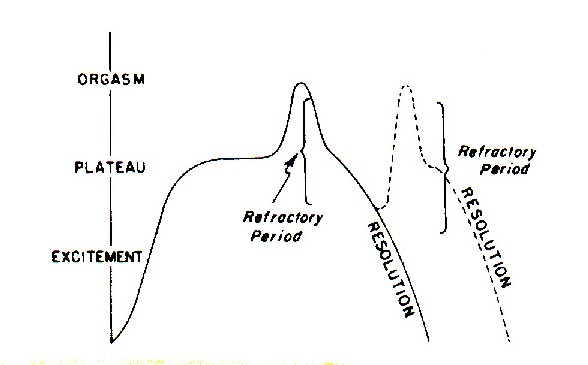

Figure 1.1a. Stages of the human male sexual response cycle

(Source W. H. Masters and V. E. Johnson, Human sexual response [Boston:

Little, Brown and Company, 1966], p. 5.) (Reprinted with the permission of

the Masters & Johnson Institute.)

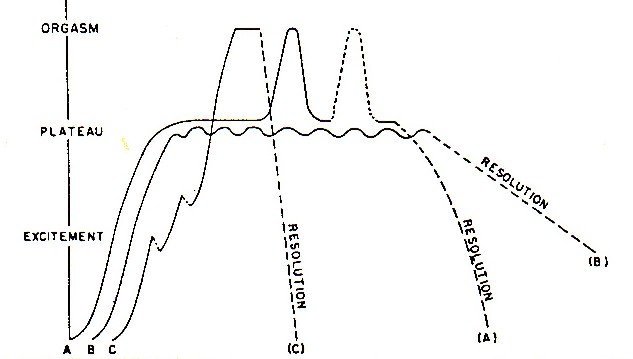

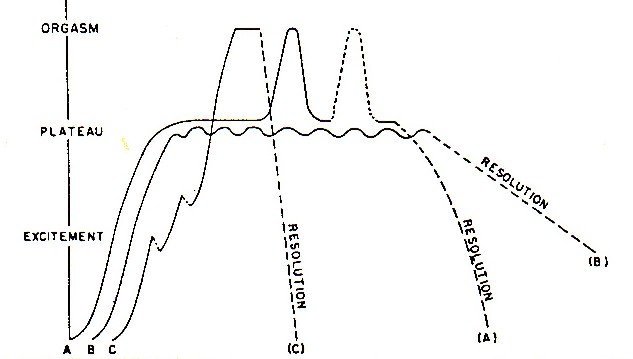

Figure 1.1b. Stages of the human female sexual response cycle

(Source: W. H. Masters and V. E. Johnson, Human sexual response [Bostonz

Little, Brown and Company, 1966], p. 5.) (Reprinted with the permission of

the Masters & Johnson Institute.)

Figure

1.2.

Relationship of phylogenetic and ontogenetic familiarity to initial-stimulus

appetence and stimulus discriminability

| |

Initial-stimulus appetence |

Stimulus discriminability |

| Philogenetic familiarity |

high |

low |

| Ontogenetic familiarity |

low |

potentially high |

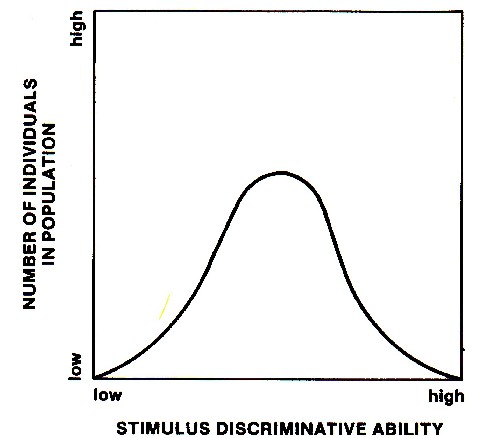

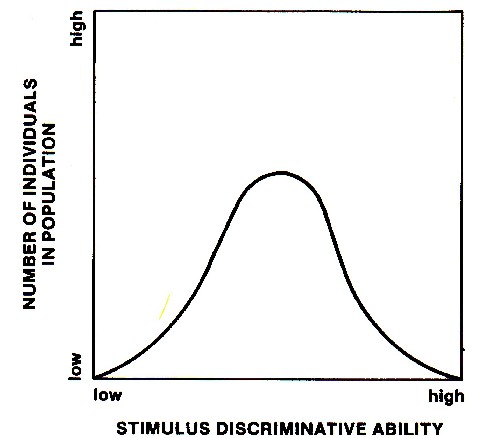

Figure 1.3.

Distribution of the trait "discriminative ability"

in a hypothetical

population.

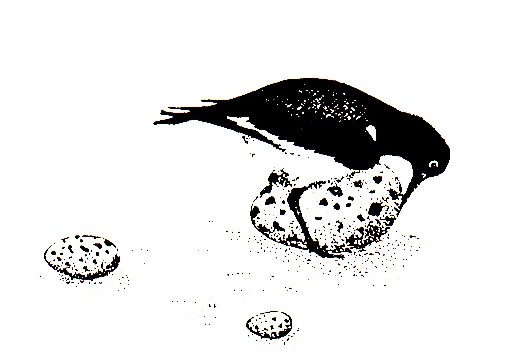

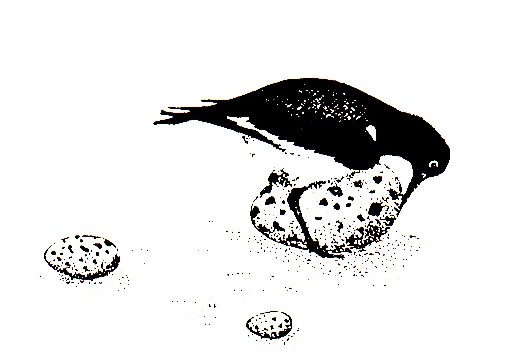

Figure 1.4.

Oystercatcher reacting to giant egg (supra-normal stimulus in preference

to normal egg (foreground) and herring gull's egg (left).

(From N. Tinbergen, The study of instinct, Oxford University Press, 1951,

p. 45. Reprinted with the permission of the publisher.) Figure 1.5

Relationship of stimulus fitness and stimulus potency to the degree of

stimulus discrimination in the perceiving individual

Figure 1.6

Relationship of total stimulus potency (or overall desirability) of a

perceived

individual to the number of near optimally-discriminated-for-fitness

stimuli by a perceiving individual.

Figure 1.7

Human heterosexual-male sexual releasing stimuli.

(a) Phylogenetically familiar, low degree of discriminableness, nubile-female shape

on the tire mudguard on an 18-wheel, semi-tractor trailer, originally advertising a

product name.

The

visual vulnerability of human males to the sexual conditioning of

ontogenetically made-familiar animate and inanimate objects and contexts

is exploited by the garment industry in the industrialized world. The

industry ~ has made lace a sexually dimorphic, female fabric (i.e., an

inanimate object) "K that has been conditioned speci?cally to sexual

arousal by being used almost exclusively on adult female lingerie and

bridal gowns. (See Figure 1.7b.) Figure 1.7b

(b) Ontogenetically familiar, highly discriminable, frequently conditioned sexual

releasing stimulus on adult female lingerie and bridal gowns.

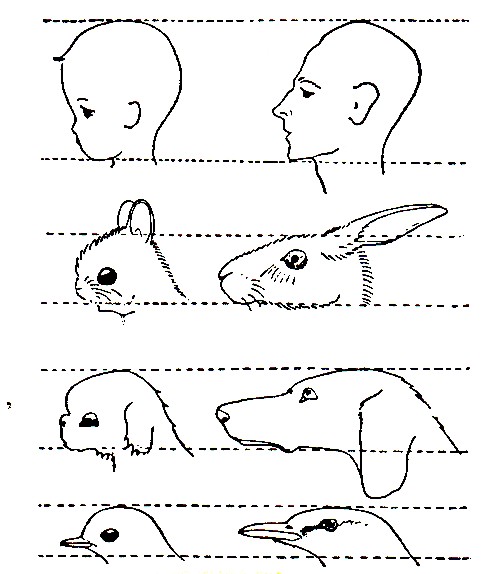

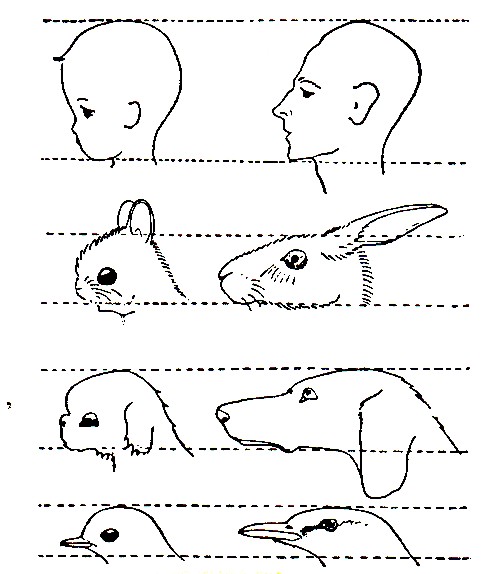

Figure 1.8

"Infant/child schema" of humans.

Left: Head proportions that are generally considered to

be "cute."

Right: Adult forms, which do not activate the drive to care for the young

(broodcare).

(From

Eibl-Eibesfeldt, 1975, p. 491 [originally published by K. Lorenz in Die

angeborenen Formen möglicher Erfahrung, Zeitschrift Tierpsychologie,

1943, 5, 235-409]. Reprinted with the permission of I. Eibl-Eibesfeldt.)

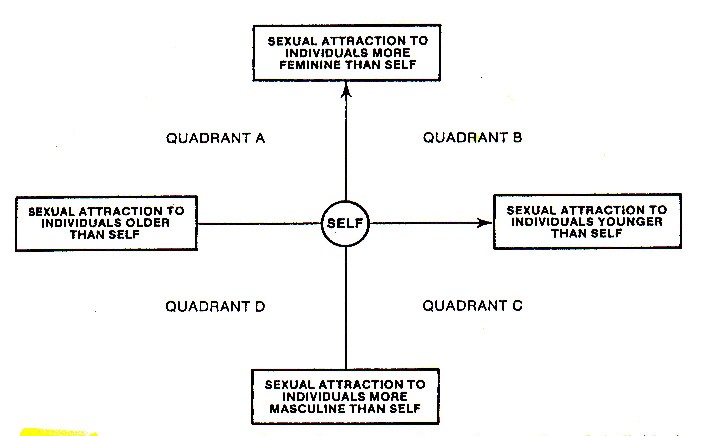

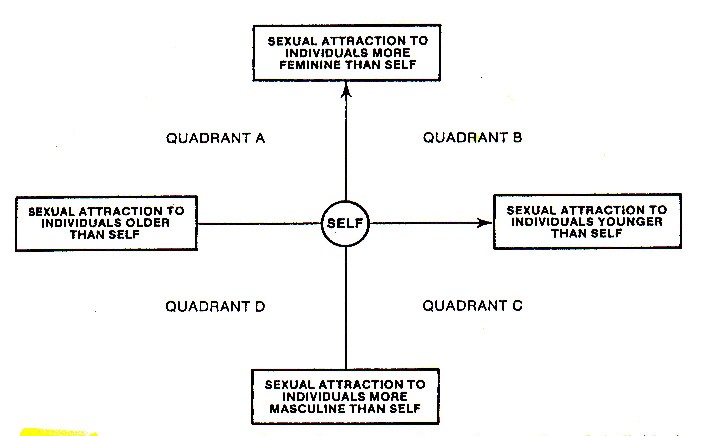

The relationship of relative age and relative gender of

individuals toward whom one is sexually attracted—represented by four

Attraction Quadrants.

(North- and East-pointing arrows are explained in caption to Figure

1.11.)

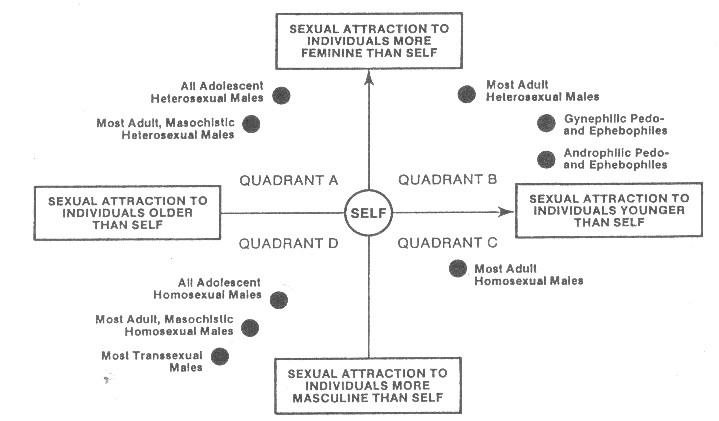

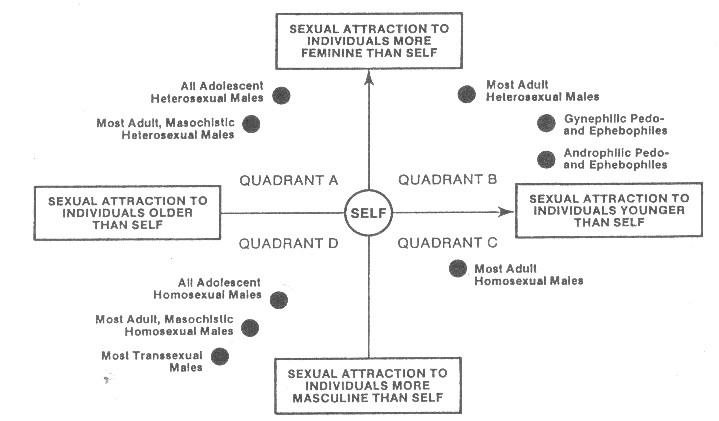

Relationship of male androphilic and gynephilic

pedophiles and ephebophiles to male individuals with other sexual

orientations and to the Attraction Quadrants of relative-age and

relative-gender attraction throughout the life span.

(North- and East-pointing arrows are explained in caption to Figure

1.11.)

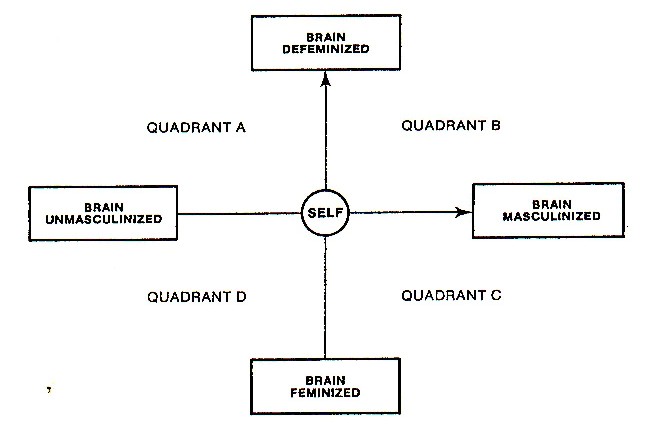

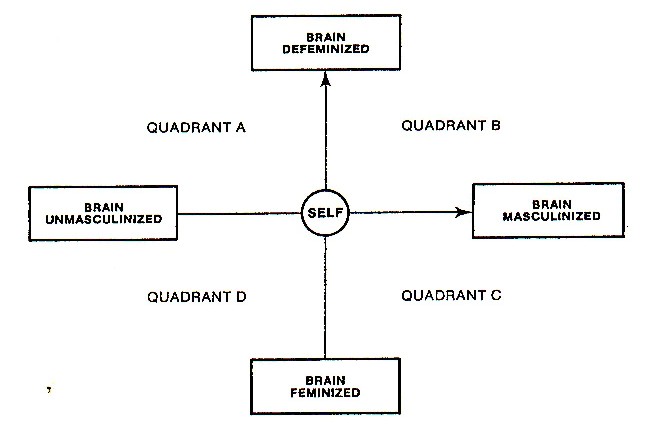

Relationship of brain masculinization and brain

defeminization in the male to relative-age and relative-gender preferences

in the four Attraction Quadrants. Compare to Figure 1.10 and see text. The

North- and East-pointing arrows signify that the brains of male (and

female) fetuses start out unmasculinized and feminized and that their

degree of masculinization and defeminization is primarily responsible for

the variance in gender-typical behavior and gender-typical sexual

attraction both within and between the two biological sexes.

|