Concealable Stigmatized Identities and Psychological Well-Being

Soc Personal Psychol Compass.

| Volume | Jan 7 |

| Issue | 1 |

| Pagination | 40–51 |

| DOI | 10.1111/spc3.12005 |

Soc Personal Psychol Compass. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2014 Jan 1.

Published in final edited form as: Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2013 Jan; 7(1): 40–51.

doi: 10.1111/spc3.12005

PMCID: PMC3664915

NIHMSID: NIHMS469629

Concealable Stigmatized Identities and Psychological Well-Being

Diane M. Quinn 1, and Valerie A. Earnshaw 2 [*See the tail of this artcle]

Abstract

Many people have concealable stigmatized identities: Identities that can be hidden from others and that are socially devalued and negatively stereotyped. Understanding how these concealable stigmatized identities affect psychological well-being is critical.

We present our model of the components of concealable stigmatized identities including valenced content – internalized stigma, experienced discrimination, anticipated stigma, disclosure reactions, and counter-stereotypic/positive information – and magnitude – centrality and salience.

Research has shown that negatively valenced content is related to increased psychological distress. However, smaller identity magnitude may buffer this distress. We review the research available and discuss important areas for future work.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[Introduction]

Each person has many different identities and attributes – gender, ethnicity, professional status, weight, parental status – that both construct and impact the self-concept. Some of these identities, such as gender and race, are clearly visible to others within an interaction. Other identities may be concealed in some social situations but not in others. For example, a medical doctor may not be identifiable while shopping at the grocery store, but would be easily identifiable when at the hospital wearing a white lab coat.

Still other identities can be concealed all the time. A person who previously had major depression but is now symptom free can not be identified by others. Notably, for many concealable identities people can choose to make the identity known to others. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered people may tell friends and family about their sexual orientation but keep the information private from co-workers.

The focus of this review is on a particular type of identity: Concealable stigmatized identities. As noted above, concealable simply means the identity can be hidden. People vary in the extent to which they conceal identities, also known as their level of “outness.”

Stigmatized also has a particular meaning. An identity that is stigmatized is socially devalued with negative stereotypes and beliefs attached to the identity (Crocker, Major, & Steele, 1998; Goffman, 1963). Moreover, stigma results in lowered power and status with resulting discriminatory outcomes (Link & Phelan, 2001).

The extent to which an identity is stigmatized can vary across different situations and within different cultural groups (Crocker et al., 1998). Examples of people with concealable stigmatized identities in the United States are

- people with mental illness (or history of mental illness),

- people with minority sexual orientations,

- people with substance abuse (or history of),

- people who have experienced domestic violence, and

- people with specific types of illnesses including HIV and many chronic illnesses (Pakenham, 2007).

Although concealable stigmatized identities are common – for example, approximately 13% of adults in the United States are treated for mental illness every year (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2009), and 50% of adults have a chronic illness (Wu & Green, 2000) – research on many of these identities has been scarce and relatively disjointed.

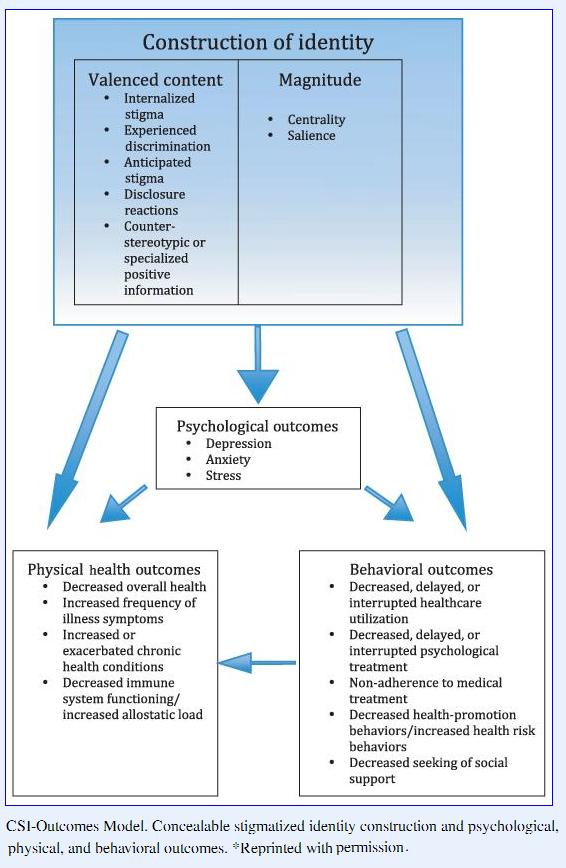

In Figure 1 we display a theoretical model of how we believe concealable stigmatized identities are related to feelings about the self, behavioral outcomes, and health outcomes.

Figure 1

CSI-Outcomes Model. Concealable stigmatized identity construction and psychological, physical, and behavioral outcomes. *Reprinted with permission.

- For more explanation of the figure and this model, see

Pachankis, John E.; The Psychological Implications of Concealing a Stigma: A Cognitive–Affective–Behavioral Model; Psychological Bulletin; 133(2), 328–345

For brevity and because the bulk of the research done on concealable stigmatized identities examines psychological well-being as an outcome variable, we will review the research relating to the top part of the figure only, or how the content of the concealable stigmatized identity within the self is related to psychological outcomes. For further review of the behavioral and physical health outcomes, as well as the public policy implications of the model, see Quinn and Earnshaw (2011).

How Does a Concealable Stigmatized Identity (CSI) Affect the Self?

Although CSIs, by definition, are devalued by the larger culture, people vary considerably in how they think and feel about their own identity. In our model, we have divided these identity-related constructs into two categories: Valenced content and magnitude.

Valenced content contains all of the affectively valenced beliefs and experiences related to the CSI. These beliefs and experiences are considered valenced because they make the person feel better or worse about the self. For example,

- some people may feel ashamed or embarrassed about the identity, whereas others do not.

- Some people may believe that others will belittle them if the identity becomes known, whereas others may expect more supportive reactions.

- Some people may have told others about the CSI and gotten a negative reaction, whereas others may have gotten a positive reaction.

All of these different feelings, thoughts, and experiences affect how people feel about themselves and these feelings, in turn, affect their psychological outcomes, including levels of depression, anxiety, and stress.

The second component in understanding how the CSI affects the self is magnitude. Magnitude captures the size of the identity within the self-concept.

- For some people the CSI is just one small, even insignificant, part of the self.

- For others, it encompasses a large part of the self, overshadowing other identities and consuming many hours of thought.

To the extent that a CSI is large in magnitude and contains negatively valenced content we expect that it will result in increased psychological distress. We next review the research evidence that links the components of a CSI to psychological outcomes.

Valenced Content and Psychological Outcomes

In the following sections, we define five different types of valenced content about one’s CSI –

- [1] internalized stigma,

- [2] experienced discrimination,

- [3] anticipated stigma,

- [4] disclosure reactions, and

- [5] specialized positive information –

and review the research on how each is related to psychological outcomes.

[1] Internalized stigma

Internalized stigma occurs when a person believes that the negative stereotypes about the identity apply to the self. A person with mental illness who believes that they are tainted and untrustworthy and that others should not trust or value them would have high internalized stigma.

Many people with CSIs are likely to have learned about and internalized negative stereotypes about their identity before the identity was obtained, making it likely that they will initially internalize these negative beliefs (Link, 1987). Stereotypes about different social identities are learned from the media (e.g., portrayal of mental illness in cartoons; Wahl, 2003), from family, and from peers (Killen, Richardson, & Kelly, 2010). If the person applies these negative believes to the self, they will believe that they are devalued or bad compared to other people.

A lot of research has shown that internalized stigma can be corrosive to the self and well-being.

A meta-analysis by Mak, Poon, Pun, and Cheung (2007) found that the average correlation between internalized stigma and mental health was ?0.33 (SD = 0.10) among people with CSIs. Studies focused on more specific elements of mental health further support this relationship.

For example, work on internalized stigma for people with minority sexual orientation (Hatzenbuehler, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Erickson, 2008), people living with HIV-AIDS (PLWHA) (Lee, Kochman, & Sikkema, 2002), and people with mental illness (Ritsher & Phelan, 2004) have all shown a relationship between internalized stigma and increased psychological distress.

Further, internalized stigma is related to increased depression among people living with mental illnesses (Ritsher, Otilingam, & Grajales, 2003), PLWHA (Lee et al., 2002; Simbayi et al., 2007; Visser, Kershaw, Makin, & Forsyth, 2008; Vyavaharkar, 2009), and sexual orientation minorities (Berghe, Dewaele, Cox, & Vincke, 2010; Herek, Gillis, & Cogan, 2009). Given that high internalized stigma signifies that a person believes negative stereotypes about the self to be true it is perhaps not surprising that greater internalized stigma is consistently related to lower psychological well-being.

[2] Experienced discrimination (enacted stigma)

Whereas internalized stigma occurs within the mind of the person with a CSI and can occur with or without anyone knowing about the identity, experienced discrimination usually requires some level of disclosure. People with CSIs may choose to tell others or they may be placed in situations where others already know about the identity (e.g., via information in medical or employment records).

In these situations, the person with the CSI may experience direct discrimination, such as being denied a job or job promotion, or given inferior health care. They may also experience more subtle social devaluation and distancing, such as avoidance by friends, family, or co-workers. People may also experience discrimination if others assume they have a stigmatized identity, even if it has not been directly disclosed. For example, teens can be bullied for appearing gay even if they are not gay and/or they have not directly disclosed this identity.

Experiences of discrimination are likely to be related to more negative psychological outcomes. Research with PLWHA (Vanable, Carey, Blair, & Littlewood, 2006), drug users (Ahren, Stuber, & Galea, 2007), and sexual minorities (Berghe et al., 2010; Mays & Cochran, 2001) has shown that experienced discrimination is related to increased depression.

Thus, whereas people who are completely “out” may experience benefits – less feelings of social isolation, the potential for more social support, greater feelings of authenticity – they may at the same time experience more direct discrimination from strangers, friends, family, and co-workers. Much more research is needed on the transition from being concealed to being largely out.

[3] Anticipated stigma

Anticipated stigma is the negative treatment people with CSIs believe they might receive if others know of their identity. Because people with CSIs are aware of the societal negative stereotypes and beliefs about people with their identity, they may expect that others will devalue them even if they have never previously experienced discrimination. Moreover, if they have already experienced discrimination due to the identity, they may be particularly likely to anticipate future stigmatizing experiences.

Our research has found that anticipated stigma is a strong predictor of psychological distress (increased depression and anxiety) among people with a variety of different CSIs (Quinn & Chaudoir, 2009). Anticipated stigma has also been shown to be related to decreased self-esteem among PLWHA (Berger, Ferrans, & Lashley, 2001).

Taken together, the three types of valenced content discussed thus far – [1] internalized, [2] experienced, and [3] anticipated stigma – are associated with increased suicide ideation and mental health problems for people with minority sexual orientation (for a review see Hatzenbuehler, 2009).

Moreover, in a sample of people with chronic illnesses, we found that both experienced stigma from healthcare providers and internalized stigma independently predicted anticipated stigma from healthcare providers (Earnshaw & Quinn, 2012). That is, people who had been treated poorly in the past by doctors, nurses, and other healthcare providers because of their illness as well as people who felt badly about themselves because of their illness expected that doctors, nurses, and other healthcare providers would treat them poorly in the future. People who anticipated greater stigma from healthcare providers, in turn, were less likely to access healthcare when they needed it. Anticipated stigma among people with chronic illness is also related to a lower overall quality of life index that includes psychological well-being (Earnshaw & Quinn, 2012).

[4] Disclosure reactions

Internalized, experienced, and anticipated stigma are all negatively valenced content but there are also ways in which the content of the CSI can be become more positively valenced. When people with a CSI choose to tell others about the identity they may receive more or less supportive reactions. Although a negative reaction could be classified under the experienced discrimination construct above, we believe that it is useful to highlight the positive, supportive, and accepting reactions people with a CSI may receive when they choose to tell another person about the identity.

These reactions from close others may have a profound affect on how the identity and self are construed. Although there is considerably less research in this area (for a review on disclosure processes see Chaudoir & Fisher, 2010), research has shown that people disclosing a CSI for the first time usually pick close others and experience positive reactions – signifying that people are generally careful in choosing a supportive confidant for the first time disclosure (Chaudoir & Quinn, 2010).

Thus, it is possible identities can be shifted in a more positive direction if the reactions of disclosure recipients are supportive (Beals, Peplau, & Gable, 2009). For example, in a study of disclosing the decision to have an abortion, Major et al. (1990) found that people who reported that the person they disclosed the abortion to was fully supportive had lower levels of depression post abortion than people who received less than full support or people who chose not to disclose at all. Likewise, research has shown that the more positive the first time disclosure experience, the less fear of disclosure and the higher self-esteem reported (Chaudoir & Quinn, 2010).

[5] Counter-stereotypic or specialized positive information

Because stigma researchers are focused on the inherently negative nature of stigma, they often do not look for the positive ways people learn to cope with and overcome stigmatized identities (cf. Crocker & Major, 1989; Thoits, 2011). Instead of simply accepting negative views of the self, people with CSIs are likely to search for ways to make positive meaning out of the negative label or experience (Park, 2010).

Two very different lines of research point to this process.

First, identity stage theories, based largely on work with minority racial identities (e.g., Cross Nigrescence Model; Cross & Vandiver, 2001) and sexual minority identities (e.g., Cass model; Cass, 1984) include an identity stage in which people search for and surround the self with positive information and role models related to the identity. This positive information is then integrated into the larger self-system.

Thus, people may go through stages from accepting and internalizing stereotypes about their identity to rejecting and fighting against these devaluing beliefs.

Recent theorizing by Thoits (2011) points to two specific strategies used by people with a history of mental illness: reflecting and challenging.

Thoits points out that instead of internalizing negative beliefs many people may choose to either directly challenge others’ negative stereotypes – through either education of the other or confrontation – or they may find ways to deflect negative stereotypes such as believing that their own mental illness is different from others or that stereotypes do not apply to their experience. These coping strategies highlight the many ways that people with CSIs may learn to minimize or distance themselves from the negative stereotypes about their identity.

[Second,] In a separate line of research on how people deal with traumatic experiences such as rape (also considered a CSI) and with life-threatening medical diagnoses (such as cancer), there is research examining “meaning making” (for review see Park, 2010). When people try to make meaning out of the difficult experiences and circumstances they have been forced to face, they can develop beliefs that the identity has led to new, positive self-qualities.

For example, in a study of people with the chronic illness multiple sclerosis (MS), Pakenham (2007) found that people indicated finding benefits with their MS identity, including having more patience, a better sense of humor, and better relationships with others. Such positive meaning-making is related to more positive psychological outcomes, including acceptance and perceptions of growth or positive life changes (Park, 2010).

Summary of valenced content

People with CSIs have a variety of different feelings and experiences related to the identity. This valenced content of the CSI is composed of [1] internalized stigma, [2] experienced discrimination, [3] anticipated stigma, [3] disclosure reactions, and [5] identity-specific counter-stereotypic or positive attributes.

These identity components contain both negative and positive feelings about the identity and it is likely that many people with a CSI will have both negative and positive self-related feelings.

Thus far, research has shown that higher levels of [1] internalized stigma, [2] experienced discrimination, and [3] anticipated stigma are related to increased psychological distress.

Less work has been done on the more positive aspects of [4] supportive disclosure reactions and [5] counter-stereotypic information, but preliminary research shows that these may be related to higher psychological well-being.

Because there is no research that examines the full valenced content for people with CSIs, it is currently not possible to determine whether one type of valenced content is more prominent in predicting outcomes or whether these components are additive or interactive.

In our own research, where we have included [1] internalized, [2] experienced, and [3] anticipated stigma, all three types of stigma uniquely predict variance in psychological distress but [4] anticipated stigma seems to be strongest predictor of behavioral outcomes (Earnshaw & Quinn, 2012; Quinn & Chaudoir, 2009). It is likely that different identities may be more or less affected by different components. Future work is needed to examine the full set of valenced content components across a variety of different CSIs.

Magnitude

People hold many different identities within the self-concept, including CSIs.

- Some CSIs are central and self-defining whereas as

- others are much more peripheral.

For example, people with one CSI (e.g., HIV+ status) may feel that their identity is more important to their sense of self than people living with another CSI (e.g., rape). Additionally, people living with the same CSI will vary in the extent to which they feel the identity is important. For example, a person with a mental illness CSI may feel the identity is crucial to who they are as a person; whereas another person with mental illness may feel that this is a relatively minor aspect of the self.

In order to capture these differences in identity magnitude we include the constructs of

- centrality – how central to one’s self-definition an identity is perceived to be – and

- salience – how often a person thinks about the identity.

Whereas centrality has been integral to work on stigmatized identities more broadly, especially work on racial identity (e.g., Crocker & Luhtanen, 1992; Sellers, Smith, Shelton, Rowley, & Chavous, 1998), salience has received very little research attention.

Centrality

Centrality captures the extent to which a person feels that a particular identity defines who they are as person. Because CSI’s are concealable, people may have greater control over how self-definitional the identity is or becomes compared to people with visible stigmatized identities.

For example, a person with a minority racial identity may not consider the racial identity to be central but they still must deal with others’ stereotypes or preconceived notions about them because their race is known to all interaction partners. A person with a CSI, however, may not face such a challenge because others do not know of the identity. Although this sounds beneficial it also worth considering that a person with a CSI who does feel the identity is central may also feel isolated or misunderstood exactly because others do not know or appreciate the identity.

In our own research with CSIs, we have found that greater centrality of the CSI is related to increased psychological distress (Quinn & Chaudoir, 2009). We speculate that this is because people with concealable identities have a difficult time finding similar others and/or do not receive support from others in their environment because the identity is not known (Frable, Platt, & Hoey, 1998).

Salience

Some people with a CSI may rarely think about their identity whereas others may think about it several times a day. This difference in frequency determines the salience of the CSI. It is important to note that salience is a measure of frequency of thoughts not of the content or valence of those thoughts. Thus thoughts about the identity could be negative, neutral, or positive, but it is the greater frequency of thoughts that make the identity more salient and increases its magnitude within the self.

There is very little research on salience with CSIs. Although research on rumination (Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991; Nolen-Hoeksema, Stice, Wade, & Bohon, 2007) and on thought suppression and intrusiveness (Smart & Wegner, 1999) are related to thought frequency, rumination measures combine negatively-valenced thoughts with frequency and work on intrusive or unwanted thoughts only measures thoughts that are unwanted rather than all thoughts about an identity (Beals et al., 2009).

It may be the case that regardless of whether a person wants to think about the CSI, some CSIs become salient

- either because there are associated symptoms (e.g., epileptic seizure)

- or behaviors (e.g., taking medications, going to AA support group)

- or even contexts (e.g., medical or psychotherapist office) that make the identity salient.

Thus some CSIs may have greater magnitude because there are associated contexts that regularly remind the person of the CSI. It is worth noting that these same contexts may also make the identity more difficult to conceal from others, thereby necessitating more thought about anticipated stigma.

In our work, increased salience at the trait level has been related to increased psychological distress (Quinn & Chaudoir, 2009). However, people may experience certain feelings or outcomes only when the context makes the identity salient.

For example, in a study of college students with a history of mental illness, it was shown that when students were reminded of their mental illness history by simply filling out a questionnaire, they performed less well on standardized test than a group with a similar mental illness history that was not reminded (Quinn, Kahng, & Crocker, 2004).

Thus, making the mental illness history salient in a context where negative stereotypes exist about the basic competency of people with mental illness was enough for students to experience a state of stereotype threat (Spencer, Steele, & Quinn, 1999; Steele & Aronson, 1995).

In our work with people with chronic illness, we have also found that certain sources of potential stigmatization – friends/family, co-workers, health care workers – are related to different levels of anticipated stigma (Earnshaw, Quinn, Kalichman, & Park, 2012). Thus, contexts of work, home, and doctor’s offices may make the CSI more or less salient.

An even larger context is the geographic region in which people live. Work by Hatzenbuehler and colleagues (Hatzenbuehler, McLaughlin, Keyes, & Hasin, 2010) has shown that in states that enacted bans on same sex marriage, the rates of mental health disorders among lesbian, bisexual, and gay people increased. Although there may be many mediating mechanisms – direct discrimination, increased negative stereotypes – the constant media attention and discussion would certainly increase salience.

Magnitude summary

In considering how a CSI may affect psychological outcomes it is important to understand the magnitude of the identity within the self. Identities can vary in how central they are considered to the self and they can also vary in their salience, or how often people think about the identity. Different social contexts are likely to impact the level of both centrality and salience that people with CSIs experience. Thus far, very little research has been done on identity magnitude with CSIs. Given the likely variability, this should be a priority for future work on concealed identities.

Conclusions

Concealed stigmatized identities can impact people’s psychological and physical well-being. Thus understanding what the important components of the identities are and how they impact the self is vital to improving people’s overall quality of life. Although stigma research within psychology has primarily focused on racial and gender identities, more recent work has begun to consider the ramifications of concealed identities and how they may differ from more visible identities.

To the extent that people have more negatively valenced content, including [1] increased internalized, [2] experienced, and [3] anticipated stigma, and [4] decreased positive disclosure reactions and [5] counter-stereotypic/positive information, they are likely to experience higher levels of psychological distress. Moreover, if the valenced content is primarily negative and the magnitude of the identity within the self is large, the impact on psychological distress will be exacerbated.

Our model draws on the general research in the social psychology of stigma (e.g., Crocker et al., 1998; Link & Phelan, 2001; Major & O’Brien, 2005) as well as on research and theory specifically on concealable stigmatized identities.

For example, Pachankis (2007) presents a comprehensive review on concealable stigma including a process model that includes situational, cognitive, and affective components of CSIs.

Likewise, the minority stress model (Meyer, 2003), includes both distal (previous prejudice events, community social support) and proximal (concealment, minority identity) events and beliefs that could affect mental health outcomes for sexual minorities.

Both of these reviews are excellent in terms of their completeness in considering potential predictors of psychological well-being. Where our model differs is in specificity. Our model focuses on content and magnitude of the identity and uses these to predict outcomes. These constructs are measurable and testable and, as reviewed throughout this paper, we have now found support for them over many different types of CSIs with both university and community samples.

The changing nature of identities

The model presented in Figure 1 should be considered only a snapshot of the relationships between CSI components and outcomes. There is no doubt that there are feedback loops between outcomes and content.

As just one example, imagine a person who has high levels of anticipated stigma about their CSI. This anticipated stigma may lead them to feel increasingly depressed and anxious. This depression, in turn, is likely to lead to increased social isolation. The person, increasingly isolated and depressed, is unlikely to disclose to others (and receive positive feedback) or to search for counter-stereotypic information about the CSI, in turn, leading to more increased distress. Thus a bi-directional feedback loop will develop between valenced content and psychological outcomes.

In a similar vein, it is important to note that both content and magnitude are likely to change over time as a person seeks new information, moves to new contexts, and adds more positively valenced content to the identity. Indeed, a recent media campaign called the “It Gets Better Project” (www.itgetsbetter.org) tries to get this very point across to GLBT teenagers. On the website, videos from GLBT adults discuss how the stigma they felt as teenagers just discovering and disclosing their identities changed and became more positive over time.

Future research directions

Much more work needs to be conducted with concealable stigmatized identities. Although many components of the CSI-outcomes model have been empirically validated, several components have yet to be thoroughly examined.

In particular, this review highlights a dearth of research on magnitude of CSIs. Researchers commonly measure valenced content of CSIs without measuring magnitude. Knowing whether the identity is central and self-defining to the self, or more peripheral, may help to explain variability in psychological outcomes among people with CSIs (see Thoits, 2011, for a discussion on mental illness and centrality).

Further, the relationship between valenced content and magnitude remains under-studied. This relationship may be interactive, with people with CSIs who have negative valenced content and strong magnitude having the worst psychological outcomes. Alternatively, valenced content and magnitude may act independently on psychological outcomes. Future research can clarify this relationship.

Further, future research should explore the changing nature of identities. The majority of studies on CSIs are cross-sectional, and therefore can only establish static relationships between variables. Longitudinal research is critical to examine feedback loops within the CSI-outcomes model as well as how valenced content and magnitude shift over time. It is likely that both valenced content and magnitude vary greatly as people gain an identity and learn to live with it. Longitudinal research will provide important insight into the development and progression of concealable stigmatized identities.

Finally, research should be conducted with an eye towards improving outcomes among people with CSIs within clinical and intervention settings. One place to start might be with strengthening understandings of the impact of counter-stereotypic or specialized positive information, and how this information can be used to improve psychological outcomes. Our review of the literature suggests that this component of valenced content is under-studied. Another important area of future research is to examine the most expedient ways in which negatively valenced content can be neutralized.

There are many people living with CSIs. They are at risk of experiencing negative psychological outcomes, which may in turn lead to negative physical health and behavioral outcomes. Although people can choose to keep their identities concealed from others, we must ensure that they have a visible presence within research. Stronger understandings of how concealable stigmatized identities are constructed within the self, including valenced content and magnitude, as well as how this construction impacts psychological outcomes can inform interventions to improve the lives of people with CSIs.

[*] Short Biographies

[*1] Diane M. Quinn’s research focuses on the experiences of members of socially stigmatized groups. Her works spans multiple types of stigmatized identities, including weight stigma, race stigma, gender stigma, and concealable stigma. She has focused on how stigmatized identities can impact psychological, behavioral, and health outcomes. Her work has appeared in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, and Psychological Science. She received her BA from the University of Virginia, her PhD from the University of Michigan, and is currently an associate professor of psychology at the University of Connecticut.

[*2] Valerie Earnshaw’s research primarily examines the relationship between stigma and health. She focuses on stigma associated with illness, including HIV/AIDS and other chronic illnesses. Her work has appeared in the Journal of Health Psychology, AIDS & Behavior, and the Encyclopedia of Behavioral Research, among other outlets. Valerie Earnshaw received her Ph.D. in social psychology from the University of Connecticut, where she also completed the Social Processes of HIV/AIDS pre-doctoral training program. She is currently a post-doctoral fellow at the Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS at Yale University.

Ahren J, Stuber J, Galea S. Stigma, discrimination and the health of illicit drug users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;88:188–196. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.10.014. [PubMed]

Beals KP, Peplau LA, Gable SL. Stigma management and well-being: The role of perceived social support, emotional processing, and suppression. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2009;35:867–879. doi: 10.1177/0146167209334783. [PubMed]

Berger BE, Ferrans CE, Lashley FR. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: Psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Research in Nursing & Health. 2001;24:518–529. doi: 10.1002/nur.10011. [PubMed]

Berghe WV, Dewaele A, Cox N, Vincke J. Minority-specific determinants of mental well-being among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2010;40:153–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2009.00567.x.

Cass VC. Homosexual identity formation: Testing a theoretical model. The Journal of Sex Research. 1984;20:143–167.

Chaudoir SR, Fisher JD. The disclosure processes model: Understanding disclosure decision making and postdisclosure outcomes among people living with a concealable stigmatized identity. Psychological Bulletin. 2010;136:236–256. doi: 10.1037/a0018193. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Chaudoir SR, Quinn DM. Revealing concealable stigmatized identities: The impact of disclosure motivations and positive first-disclosure experiences on fear of disclosure and well-being. Journal of Social Issues. 2010;66:570–584. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2010.01663.x.

Crocker J, Luhtanen R. A collective self-esteem scale: Self-evaluation of one’s social identity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1992;18:302–318.

Crocker J, Major B. Social stigma and self-esteem: The self-protective properties of stigma. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;96:608–630.

Crocker J, Major B, Steele CM. Social stigma. In: Gilbert DT, Fiske ST, editors. The Handbook of Social Psychology. 4th edn Vol. 2. Mcgraw-Hill; Boston, MA: 1998. pp. 504–553.

Cross WE, Jr, Vandiver BJ. Nigrescence theory and measurement: Introducing the cross racial identity scale (CRIS) In: Alexander CM, editor. Handbook of Multicultural Counseling. 2nd edn Sage Publications, Inc; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2001. pp. 371–393.

Earnshaw VA, Quinn DM. The impact of stigma in healthcare on people living with chronic illnesses. Journal of Health Psychology. 2012;17:157–168. doi: 10.1177/1359105311414952. [PubMed]

Earnshaw VA, Quinn DM, Kalichman SC, Park CL. Development and psychometric evaluation of the chronic illness anticipated stigma scale. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10865-012-9422-4. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Frable DE, Platt L, Hoey S. Concealable stigmas and positive self-perceptions: Feeling better around similar others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:909–922. [PubMed]

Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Prentice Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1963.

Hatzenbuehler ML. How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological medication framework. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;145:707–730. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. The impact of institutional discrimination on psychiatric disorders in lesbian, gay, and bisexual population: A prospective study. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:452–459. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.168815. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Hatzenbuehler ML, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Erickson SJ. Minority stress predictors of HIV risk behavior, substance use, and depressive symptoms: Results from a prospective study of bereaved gay men. Health Psychology. 2008;27:455–462. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.4.455. [PubMed]

Herek GM, Gillis JR, Cogan JC. Internalized stigma among sexual minority adults: Insights from a social psychological perspective. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2009;56:32–43. doi: 10.1037/a0014672; 10.1037/a0014672.supp (Supplemental)

Killen M, Richardson CB, Kelly MC. Developmental perspectives. In: Dovidio JF, Hewstone M, Glick P, Esses VM, editors. The Sage Handbook of Prejudice, Stereotyping, and Discrimination. Sage; Los Angeles, CA: 2010. pp. 97–114.

Lee RS, Kochman A, Sikkema KJ. Internalized stigma among people living with HIV-AIDS. AIDS and Behavior. 2002;6:309–319.

Link BG. Understanding labeling effects in the area of mental disorders: An assessment of the effects of expectations of rejection. American Sociological Review. 1987;52:96–112.

Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology. 2001;27:363–385.

Major B, Cozzarelli C, Sciacchitano AM, Cooper ML, Testa M, Mueller PM. Perceived social support, self-efficacy, and adjustment to abortion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;59:452–463. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.59.3.452. [PubMed]

Major B, O’Brien LT. The social psychology of stigma. Annual Review of Psychology. 2005;56:393–421. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070137. [PubMed]

Mak WWS, Poon CYM, Pun LYK, Cheung SF. Meta-analysis of stigma and mental health. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;65:245–261. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.015. [PubMed]

Mays VM, Cochran SD. Mental health correlates of perceived discrimination among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:1869–1876. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:674–697. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J. A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: The 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61:115–121. [PubMed]

Nolen-Hoeksema S, Stice E, Wade E, Bohon C. Reciprocal relations between rumination and bulimic, substance abuse, and depressive symptoms in female adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:198–207. [PubMed]

Pakenham KI. The nature of benefit finding in multiple sclerosis (MS) Psychology, Health, & Medicine. 2007;12:190–196. doi: 10.1080/13548500500465878. [PubMed]

Pachankis, John E.; The Psychological Implications of Concealing a Stigma: A Cognitive–Affective–Behavioral Model; Psychological Bulletin; 133(2), 328–345 [PubMed]

Park CL. Making sense of the meaning literature: An integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events. Psychological Bulletin. 2010;136:257–301. doi: 10.1037/a0018301. [PubMed]

Quinn DM, Chaudoir SR. Living with a concealable stigmatized identity: The impact of anticipated stigma, centrality, salience, and cultural stigma on psychological distress and health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;97:634–651. doi: 10.1037/a0015815. [PubMed]

Quinn DM, Kahng SK, Crocker J. Discreditable: Stigma effects of revealing a mental illness history on test performance. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2004;30:803–815. [PubMed]

Quinn DM, Earnshaw VA. Understanding concealable stigmatized identities: The role of identity in psychological, physical, and behavioral outcomes. Social Issues and Policy Review. 2011;5:160–190.

Ritsher JB, Otilingam PG, Grajales M. Internalized stigma of mental illness: Psychometric properties of a new measure. Psychiatry Research. 2003;121:31–49. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2003.08.008. [PubMed]

Ritsher JB, Phelan JC. Internalized stigma predicts erosion of morale among psychiatric outpatients. Psychiatry Research. 2004;129:257–265. [PubMed]

Sellers RM, Smith MA, Shelton JN, Rowley SAJ, Chavous TM. Multidimensional model of racial identity: A reconceptualization of African American racial identity. Personality & Social Psychology Review. 1998;2:18. [PubMed]

Simbayi LC, Kalichman S, Strebel A, Cloete A, Henda N, Mqeketo A. Internalized stigma, discrimination, and depression among men and women living with HIV/AIDS in Cape Town, South Africa. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;64:1823–1831. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.01.006. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Smart L, Wegner DM. Covering up what can’t be seen: Concealable stigma and mental control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77:474–486. [PubMed]

Spencer SJ, Steele CM, Quinn DM. Stereotype threat and women’s math performance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1999;35:4–28.

Steele CM, Aronson J. Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African-Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:797–811. [PubMed]

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Results from the 2008 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Rockville, MD; 2009. Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-36, HHS Publication No. SMA 09-4434.

Thoits PA. Resisting the stigma of mental illness. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2011;74:6–28.

Vanable PA, Carey MP, Blair DC, Littlewood RA. Impact of HIV-related stigma on health behaviors and psychological adjustment among HIV-positive men and women. AIDS and Behavior. 2006;10:473–482. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9099-1. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Visser MJ, Kershaw T, Makin JD, Forsyth BWC. Development of parallel scales to measure HIV-related stigma. AIDS and Behavior. 2008;12:759–771. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Vyavaharkar M. The relationships between depression and HIV-related stigma, disclosure of HIV-positive status, and social support among African-American women with HIV disease living in the rural southeastern united states. ProQuest Information & Learning) Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering. 2009;69 2009-99100-316.

Wahl OF. Depictions of mental illnesses in children’s media. Journal of Mental Health. 2003;12:249–258. doi: 10.1080/0963823031000118230.

Wu SY, Green A. Projection of Chronic Illness Prevalence and Cost Inflation. RAND Health; Santa Monica, CA: 2000.